Changes in appearance and in display of formulas, tables, and text may have occurred during translation of this document into an electronic medium. This HTML document may not be an accurate version of the official document and should not be relied on.

For an official paper copy, contact the Florida Public Service Commission at contact@psc.state.fl.us or call (850) 413-6770. There may be a charge for the copy.

|

|

|

||

|

DATE: |

|||

|

TO: |

Office of Commission Clerk (Cole) |

||

|

FROM: |

Office of the General Counsel (Brown) Division of Engineering (Rieger) |

||

|

RE: |

|||

|

AGENDA: |

05/14/13 – Regular Agenda – Proposed Agency Action for Issues 3-5– Interested Persons May Participate – Motion to Dismiss – No oral argument requested. |

||

|

COMMISSIONERS ASSIGNED: |

|||

|

PREHEARING OFFICER: |

|||

|

SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS: |

None |

||

|

FILE NAME AND LOCATION: |

|||

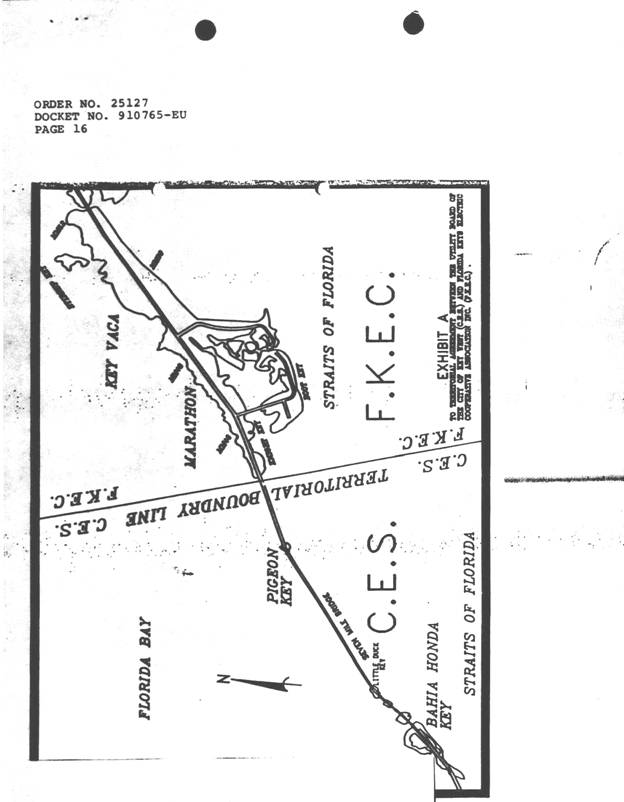

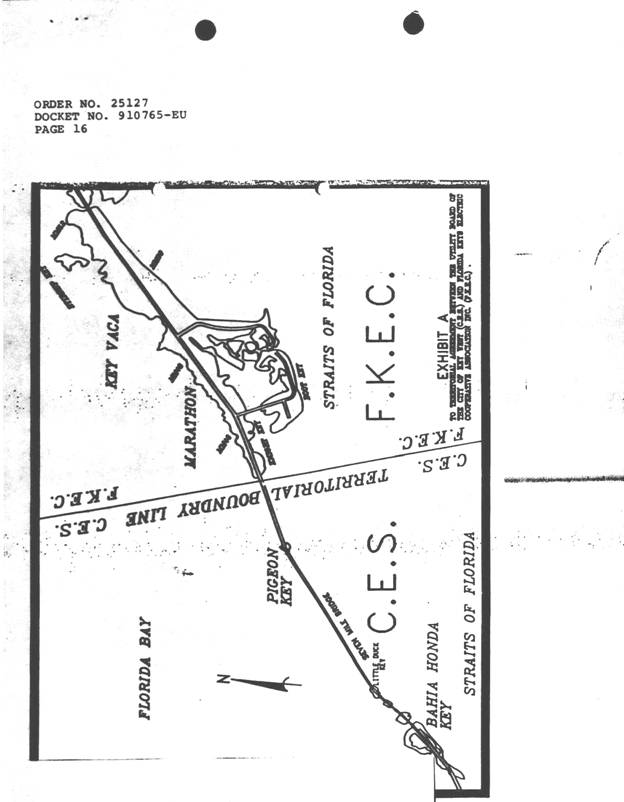

On September 27, 1991, the Commission approved a Territorial Agreement (Agreement) between the municipal utility of the City of Key West, presently d/b/a Keys Energy Services (Keys Energy), and the Florida Keys Rural Electric Cooperative (Cooperative), by Order No. 25127, in Docket No. 910765-EU, In re: Joint petition of Florida Keys Electric Cooperative Association, Inc. and the utility board of the City of Key West for approval of a territorial agreement. (Attachment A) The Agreement was attached to the Order and incorporated therein. It delineated the service territories for the two utilities operating in the Florida Keys, and established a 30-year term. By the terms of the Agreement, and the map included in it, the Cooperative agreed to provide electric service to customers from Key Largo to Knight Key, and Keys Energy agreed to provide electric service to customers from Key West to Pigeon Key. The residents of No Name Key, which lies within Keys Energy’s service territory, do not currently receive electric service from the utility. Electric power is provided by customer owned solar panels and generators. At present there are approximately 43 residences on No Name Key, the majority of which were constructed in the 1950’s. Further development is not expected because No Name Key is designated a critical barrier island, and most of the island is federally protected land, home to Key Deer and other endangered species.

Some of the property owners on No Name Key have asked Keys Energy to provide electric service to their property, and they have agreed to pay Keys Energy approximately $700,000 in Contributions in Aid of Construction to extend the necessary distribution facilities to the island across a bridge from nearby Big Pine Key. After some delay caused by Keys Energy’s uncertainty whether Monroe County (County) could prohibit Keys Energy from providing service to the island, Keys Energy began construction of the facilities, and completed the project in July 2012.

On March 5, 2012, Robert D. Reynolds and Julianne C. Reynolds, the owners of residential property on No Name Key, Florida, filed a complaint against Keys Energy for failure to provide electric service to their residence as required by the terms of the Territorial Agreement that the Commission approved in 1991. The Reynolds filed an amended complaint against Keys Energy on March 13, 2013, to reflect the fact that Keys Energy had installed electric facilities on No Name Key but had not yet provided service to customers because the County refused to issue building permits to the customers to connect their homes to the Keys Energy facilities.[1] The amended complaint asserts that the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction to interpret the territorial agreement it approved and determine whether property owners on No Name Key are entitled to electric service from Keys Energy. Essentially, the amended complaint asks the Commission to determine that the existing property owners on No Name Key who have requested electric service are entitled to receive it from Keys Energy, which the County cannot prohibit by the application of its local comprehensive plan or other ordinances.[2] Keys Energy filed a Response and Affirmative Defenses to the Reynolds’ Amended Complaint on April 8, 2013 in which it asserted that it had entered into a contract with the Association for the construction of facilities to provide electric service to the island. Keys Energy also asserted that the facilities had been constructed and were ready to provide service. Monroe County filed a Motion to Dismiss the amended complaint on April 1, 2013, and the Reynolds filed their opposition to the Motion to Dismiss on April 8, 2013.[3]

The controversy over whether No Name Key property owners should receive electric service from Keys Energy began long before the Reynolds filed their complaint with this Commission. Most recently, the County filed a complaint for a declaratory judgment and injunctive relief against Keys Energy and the No Name Key property owners in the 16th Judicial Circuit Court for Monroe County.[4] The County asked the Circuit Court to determine whether the County could preclude Keys Energy from providing electric service to the island. The Circuit Court allowed the Commission to file an Amicus Curiae brief in the case, in which the Commission suggested to the Court that it has exclusive jurisdiction to resolve the issue, or at the very least it has jurisdiction to determine the scope of its jurisdiction in the first instance. The Circuit Court dismissed the County’s action with prejudice, holding that the Commission does have exclusive jurisdiction to determine whether Keys Energy should provide electric service to No Name Key property owners. The Circuit Court’s decision was affirmed in Alicia Roemmele-Putney, et. al. v. Robert D. Reynolds. et. al., 106 So. 3d 78, 82 (Fla. 3d DCA 2013). The Commission was permitted to file a similar Amicus Curiae brief in that appeal. In its opinion, the Third District Court of Appeal stated that the Commission is to determine the scope of its own jurisdiction over the No Name Key controversy. The Third District also stated that:

The appellees and the PSC also have argued, and we agree, that KES’s existing service and territorial agreement (approved by the PSC in 1991) relating to new customers and ‘end use facilities’ is subject to the PSC’s statutory power over all ‘electric facilities’ and any territorial disputes over service areas, pursuant to section 366.04(2)(e), Florida Statutes (2011). The PSC’s jurisdiction, when properly invoked (as here) is ‘exclusive and superior to that of all other boards, agencies, political subdivisions, municipalities, towns, villages, or counties.’

Shortly after the Third District issued its decision, the Circuit Court in Monroe County dismissed another complaint for declaratory judgment and injunctive relief filed by the County regarding essentially the same subject matter as the first complaint. This time the Circuit Court dismissed the complaint without prejudice, stating that once the Commission has decided the matters within its jurisdiction, the Circuit Court would be available to address any remaining issues. The Circuit Court quoted State v. Willis, 310 So. 2d 1, 3 (Fla. 1975) as follows:

Where the Public Service Commission, or this Court (Florida Supreme Court) on review, has disposed and completed a matter coming within the Commission’s jurisdiction, subsequent unresolved claims or causes arising against the affected regulated carrier or utility which are not statutorily remediable by the Commission and lie outside its jurisdiction may be litigated in the appropriate civil courts.

After the Third District issued its decision confirming that the Commission has jurisdiction to determine whether the No Name Key customers were entitled to receive electric service from Keys Energy, the Prehearing Officer issued an Order Establishing Schedule for Briefs on Certain Legal Issues.[5] The Prehearing Officer determined that two legal issues were fundamental and central to the resolution of this case, and a Commission decision on those issues would facilitate the identification of any factual disputes in an evidentiary hearing to follow, if

one would be necessary at all after the legal issues were resolved.[6] The Reynolds, Monroe County, and Ms. Roemmele-Putney filed briefs on the issues on April 19, 2013. The Association filed a Notice of Joinder adopting the Reynolds’ brief on April 23, 2013. The issues are:

1. Does the Commission have jurisdiction to resolve the Reynolds’ complaint?

2. Are the Reynolds and No Name Key property owners entitled to receive electric power from Keys Energy under the terms of the Commission’s Order No. 25127 approving the 1991 territorial agreement between Keys Energy and the Florida Keys Electric Cooperative?

This recommendation addresses those issues, Monroe County’s Motion to Dismiss the Reynolds second amended complaint for lack of standing and for failure to state a cause of action upon which relief can be granted, and the appropriate disposition of the Reynolds’ complaint. This recommendation has been revised to include additional Issue A, addressing Ms. Roemmele-Putney’s Motion for Stay pending appellate review of Order No. PSC-13-0161-PCO-EM denying her petition to intervene.

The Commission has jurisdiction over this matter pursuant to Section 366.04 and 366.05, Florida Statutes (F.S.).

Issue A has been added to the original Recommendation filed May 2, 2013:

Issue A:

Should the Commission grant Ms. Roemmele Putney’s Motion for Stay of Proceedings?

Recommendation:

No. The Commission should deny the motion. The motion does not meet the established criteria for a stay pending judicial review set out in Rule 25-22.061, F.A.C.

Staff Analysis:

The Motion for Stay

On May 7, 2013, pursuant to Section 120.68(3), F.S., and Rule 9.190(e)(2), Florida Rules of Appellate Procedure (Fla.R.App.P.), Ms. Roemmele-Putney filed a Motion for Stay of this proceeding pending judicial review of the Prehearing Officer’s denial of her petition to intervene in the docket. Contemporaneously, Ms. Roemmele-Putney filed a Petition for Expedited Review of Non-Final Action by Public Service Commission Hearing Officer with the Florida Supreme Court. In her Motion for Stay, Ms. Roemmele-Putney asserts that: (1) a stay will minimize unnecessary expenditure of the parties’ and the Commission’s resources; (2) she will be prejudiced if the case proceeds without her participation as an intervenor to establish a proper record, and; (3) no parties will be prejudiced by a stay because no final order may be issued with an appeal of a non-final order pending.

The Reynolds’ Opposition to the Motion for Stay

On May 8, 2013, the Reynolds filed an opposition to the motion, arguing that it should be denied because Ms. Roemmele-Putney has been permitted to participate fully in the proceeding, including participation in all informal conference calls, submitting an initial brief, and participation in the upcoming Agenda Conference, and therefore she has not been prejudiced. The Reynolds also argue that a stay of an action during interlocutory review is discretionary, and the Commission should consider the expenses that all the parties will incur to attend the May 14, 2013 Agenda Conference, which will be wasted and cause the parties financial hardship if the Commission stays a decision on the substantive issues.

Standard of Review

Section 120.68(3), F.S., provides that the filing of a petition for judicial review of an agency action does not itself stay enforcement of the agency decision, but Rule 9.190(e)(2)(A), Fla.R.App.P. provides for a stay under Chapter 120, F.S., the Administrative Procedures Act, as follows:

A party seeking to stay administrative action may file a motion either with the lower tribunal or, for good cause shown, with the court in which the notice or petition has been filed. The filing of the motion shall not operate as a stay. The lower tribunal or court may grant a stay upon appropriate terms. Review of orders entered by lower tribunals shall be by the court on motion.

Commission Rule 25-22.061(2), F.A.C., Stay Pending Judicial Review, provides the Commission’s criteria for considering whether to grant a stay:

. . . [A] party seeking to stay a final or nonfinal order of the Commission pending judicial review may file a motion with the Commission, which has authority to grant, modify, or deny such relief. A stay pending review granted pursuant to this subsection may be conditioned upon the posting of a good and sufficient bond or corporate undertaking, other conditions relevant to the order being stayed, or both. In determining whether to grant a stay, the Commission may, among other things, consider:

(a) Whether the petitioner has demonstrated a likelihood of success on the merits on appeal;

(b) Whether the petitioner has demonstrated a likelihood of sustaining irreparable harm if the stay is not granted;

(c) Whether the delay in implementing the order will likely cause substantial harm or be contrary to the public interest if the stay is granted.

Analysis

In her Motion for Stay, Ms. Roemmele-Putney has not demonstrated a likelihood of success on appeal or a likelihood of sustaining irreparable harm. Ms. Roemmele-Putney does not address these issues in her motion to stay, other than to say she will be prejudiced if the stay is not granted. Staff’s review of these questions, however, indicates that Ms. Roemmele-Putney’s Petition for Expedited Review of Non-Final Action denying her intervention has very little, if any, likelihood of success before the Court, and she will not be irreparably harmed because she will have an adequate remedy on appeal when the case is finished.

This is the primary principle governing judicial consideration of nonfinal agency action: whether or not the petitioner would have an adequate remedy on appeal of the final agency action. Section 120.68(1), F.S. clearly articulates this principle:

A party who is adversely affected by final agency action is entitled to judicial review. A preliminary, procedural, or intermediate order of the agency or of an administrative law judge of the Division of Administrative Hearings is immediately reviewable if review of the final action would not provide an adequate remedy.

Procedural orders denying intervention are properly reviewable by appeal of the final agency action, not before. Charter Medical-Jacksonville, Inc. v, Community Psychiatric Centers of Florida, Inc., and Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services, 482 So. 2d 437 (Fla. 1st DCA 1985). In that case, the appellant sought interlocutory review of the Department of Health’s denial of its petition for intervention. The First District Court of Appeal held that the appellant was not entitled to immediate review because the appellant did not show that review after final agency action would provide inadequate relief. The Court did say that the appellant could seek review after final agency action. See also, Ameristeel Corporation, f/k/a Florida Steel Corporation v. Clark, 691 So. 2d 473 (Fla. 1997), where the Supreme Court considered the Commission’s denial of Ameristeel’s petition to intervene on appeal from the Commission’s final order approving a modification to a territorial agreement between Florida Power & Light Company and Jacksonville Electric Authority. The Court had previously denied Ameristeel’s request for interlocutory review in Florida Steel Corporation v. Clark, 675 So. 2d 927 (Fla. 1996). Ms. Roemmele-Putney is also not likely to succeed on the merits of her challenge to Order No. PSC-13-0161-PCO-EM denying intervention, because that Order complied with the essential requirements of law. It appropriately applied the standard for intervention prescribed in Agrico Chemical Company v. Department of Environmental Regulation, 406 So. 2d 478, 482 (Fla. 2nd DCA 1981), finding Ms. Roemmelle-Putney suffered no injury in fact of a kind this proceeding was designed to protect.

Staff believes that there will be substantial harm to the parties and interested persons who plan to attend the Agenda Conference if the stay is granted. Several Monroe County attorneys, the Reynolds’ attorney, the Association’s attorney and its president, a representative from Keys Energy, and residents of the island will waste time and financial resources on travel and hotel arrangements if the Commission issues a stay at the Agenda. Conversely, staff believes that Ms. Roemmele-Putney will not be irreparably harmed if the Commission proceeds to address the substantive issues of the case. As the Reynolds point out, Ms. Roemmele-Putney has participated fully in the case, and she will be able to participate at the Agenda Conference as well. Considering that Ms. Roemmele-Putney’s petition for interlocutory relief before the Court is not likely to succeed, further delay of this case is harmful and unnecessary, and staff recommends that Ms. Roemmele-Putney’s Motion for Stay should be denied.

Issue 1:

Should the Commission entertain oral argument on Monroe County’s Motion to Dismiss?

Recommendation:

No. Oral Argument was not requested pursuant to Rule 25-22.0022, Florida Administrative Code (F.A.C.). The Commission does have the discretion, however, to allow oral argument if it so chooses. (M. Brown)

Staff Analysis:

Rule 25-22.0022, F.A.C., provides, in pertinent part:

(1) Oral argument must be sought by separate written request filed concurrently with the motion on which argument is requested, or no later than 10 days after exceptions to a recommended order are filed. Failure to timely file a request for oral argument shall constitute waiver thereof. Failure to timely file a response to the request for oral argument waives the opportunity to object to oral argument. The request for oral argument shall state with particularity why oral argument would aid the Commissioners, the Prehearing Officer, or the Commissioner appointed by the Chair to conduct a hearing in understanding and evaluating the issues to be decided, and the amount of time requested for oral argument.

(2) The Commission may request oral argument on matters over which it presides. . .

Neither the County nor the Reynolds requested oral argument on the County’s Motion to Dismiss. While staff does not recommend oral argument be granted because the parties did not comply with the rule, the Commission can entertain oral argument, in its discretion, if it believes that oral argument would assist it in understanding and evaluating the issues to be decided. If the Commission does decide to hear oral argument on the motion, Staff recommends that 5 minutes be allotted to each side.

Issue 2:

Should the Commission deny the County’s Motion to Dismiss the Reynolds’ Amended Complaint?

Recommendation:

Yes. The Commission should deny the County’s Motion to Dismiss the Amended Complaint. The complaint states a cause of action upon which relief can be granted. (M. Brown)

Staff Analysis:

Standard of Review

A motion to dismiss challenges the legal sufficiency of the facts alleged in a petition. The standard to be applied in disposing of a motion to dismiss is whether, with all the allegations in the petition assumed to be true, the petition states a cause of action upon which relief can be granted. Meyers v. City of Jacksonville, 754 So. 2d 198, 202 (Fla. 1st DCA 2000). When making this determination, only the petition and documents incorporated therein can be reviewed, and all reasonable inferences drawn from the petition must be made in favor of the petitioner. Vanes v. Dawkins, 624 So. 2d 349, 350 (Fla. 1st DCA 1993); Flyer v. Jeffords, 106 So. 2d 229 (Fla. 1st DA 1958), overruled on other grounds, 153 So. 2d 759, 765 (Fla. 1st DCA 1963).

The Reynolds’ Complaint

In their complaint the Reynolds assert that property owners on No Name Key have tried to bring about the extension of commercial electric service to No Name Key for decades without success. They state that the overwhelming majority of the 43 potential customers on the island desire service from Keys Energy:

because of the high costs associated with using alternative energy sources, and the inability to dispose of by-products of alternative energy, including exhausted batteries and damaged or worn propane tanks. More so, the use of large diesel fuel generators produces large amounts of environmental and noise pollutants, affecting all aspects of the ecosystem unique to No Name Key. By connecting to commercial electrical power, the combined use of the existing solar capability together with commercial grade power would result in positive net solar metering producing a net positive impact on the environment. The net positive impact would far exceed the negative impacts which currently exist as a result of the current pollutants emitted to power the homes on No Name Key.

Amended Complaint, pps. 5-6.

The Reynolds allege that Keys Energy has failed to provide electric service to them and to other property owners on No Name Key pursuant to the terms of Keys Energy’s own charter and the territorial agreement between Keys Energy and Keys Electric Rural Cooperative that the Commission approved in 1991.[7] They assert that the territorial agreement provides that the utility parties to the agreement have an obligation to initiate electric service to customers in their respective service areas delineated in Section 6.1 of the agreement. The Reynolds further assert that they and other property owners have paid for the construction and installation of distribution lines to their properties, and Keys Energy has now constructed the facilities to provide service. Keys Energy has not yet provided service, however, because Monroe County claims that its comprehensive plan and land development ordinances prohibit the extension of utility service to No Name Key, and preclude No Name Key customers from connecting to Keys Energy’s facilities.[8] The Reynolds claim that Monroe County has refused to issue building permits to install a 200 AMP Electric Service and Subfeed to their home, which they need in order to receive electric service from Keys Energy.

The Reynolds contend that the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction to determine whether they are entitled to receive electric service under the terms of the 1991 territorial agreement, and to implement and enforce that agreement against Keys Energy. They cite the territorial agreement itself, and Section 366.04, F.S., as support for their position. That statute provides that the Commission has the jurisdiction “[t]o require electric power conservation and reliability within a coordinated grid throughout Florida for operational and emergency purposes,” Section 366.04(2)(c), F.S.; “[t]o approve territorial agreements between and among rural electric cooperatives, municipal electric utilities, and other electric utilities under its jurisdiction,” Section 366.04(2)(d), F.S.; and “shall further have jurisdiction over the planning, development, and maintenance of a coordinated electric power grid throughout Florida to assure an adequate and reliable source of energy for operational and emergency purposes in Florida . . . .” Section 366.04(5), F.S. The statute further provides that:

[t]he jurisdiction conferred upon the commission shall be exclusive and superior to that of all boards, agencies, political subdivisions, municipalities, towns, villages, or counties, and, in each case of conflict therewith, all lawful acts, orders, rules and regulations of the commission shall in each instance prevail.

Section 366.04(1), F.S.

The Reynolds ask the Commission to: exercise jurisdiction over the subject matter of this action, determine that its jurisdiction preempts Monroe County’s enforcement of Ordinance 043-2001 as it applies to Keys Energy’s provision of electric service to No Name Key customers, determine that the commercial electrical distribution lines Keys Energy extended to No Name Key customers are legally permissible and properly installed, order Keys Energy to provide electric service to No Name Key, and determine that Monroe County cannot withhold building permits from Keys Energy’s customers based solely on the location of their property on No Name Key.

Monroe County’s Motion to Dismiss

The County argues that the Reynolds’ complaint should be dismissed with prejudice because they lack standing to bring an action under the Territorial Agreement that the Commission approved in Order No. 25127.[9] According to the County, Section 7.2 of the Territorial Agreement expressly provides that it does not confer or give any benefits to any person other than Keys Energy and Florida Keys Electric Cooperative. Section 7.2 reads as follows:

Nothing in this agreement, express or implied, is intended, or shall be construed, to confer upon or give to any person other than the parties hereto, or their respective successors or assigns, any right, remedy, or claim under or by reason of this Agreement, or any provision or condition hereof; and all of the provisions, representations, covenants, and conditions herein contained shall inure to the sole benefit of the Parties or their respective successors or assigns.

Order No. 25127, p. 13. The County contends that under the principle that territorial agreements merge into and become part of Commission orders, Order No. 25127 itself bars the Reynolds from seeking relief under that Agreement.

The County also argues that the Reynolds have failed to state a claim upon which the Commission can grant relief, because none of the statutory provisions the Reynolds cited confers a right to service on customers of Keys Energy or imposes an affirmative obligation to serve on Keys Energy itself. According to the County, the bases for relief in the Complaint “are grounded almost entirely on two separate legislative acts, Chapter 163, Florida Statutes, and Chapter 69-1191, Laws of Florida,” and those laws do not impose upon Keys Energy an obligation to serve or confer a right to service from Keys Energy “on any would-be customer.” Motion to Dismiss p. 7. The County also points out that neither Chapter 163, F.S., nor Chapter 69-1191, Laws of Florida, Keys Energy’s enabling legislation, confer any jurisdiction on the Commission.

Next the County contends that the Commission’s “Grid Bill” authority imposes no obligation to serve or right to service from Keys Energy. The County asserts that the Reynolds’ attempt to invoke Section 366.04, F.S., as the basis for their claims “is at best over-reaching and misplaced, for the simple reason that the referenced statute does not address any utility’s obligation to serve or any customer’s right to service. . . .” Motion to Dismiss, p. 11.

For the above reasons, the County asserts that the Reynolds’ complaint does not pass the Agrico[10] test for standing because they have failed to show a substantial interest of a type this proceeding is designed to protect. The County asserts that “they cannot articulate any statutory basis for the claimed relief. Without a statutory basis for the claimed relief, the Agrico ‘zone of interest’ test cannot be satisfied,” and “they fail to provide the required explanation of how the relief requested is supported by the statutes invoked.” Motion to Dismiss, pps. 12, 13.

The Reynolds’ Response in Opposition to the Motion

The Reynolds state that in the instant case, they have asked the Commission to determine that Keys Energy can extend its electric lines to customers on No Name Key and that Monroe County cannot prohibit them from connecting their homes to those lines. According to the Reynolds, the Motion to Dismiss should be denied because the County has ignored the Third District Court of Appeal’s decision in the Roemmele-Putney case,[11] other pertinent provisions of the Territorial Agreement, and the complaint provisions of Commission Rule 25-22.036, F.A.C.

According to the Reynolds, the District Court held that the subject matter of their complaint was within the Commission’s exclusive jurisdiction, and thus the District Court’s decision limited the forum in which the Reynolds can raise their claims for electric service from Keys Energy to the Commission’s proceeding. The District Court, the Reynolds claim, found that Keys Energy’s existing service, relation to new customers, and its end use facilities were all subject to the Commission’s statutory power over “electric utilities”.

The Third District’s holding is grounded in the conclusion that Fla. Stat. 366.04(5) has granted the [Commission] jurisdiction over the planning, development, maintenance of the electric grid.[12] This is one of the bases of approving the Territorial Agreement by and between [Keys Energy] and the Florida Keys Electric Co-op. See PSC Order 25127 (‘the agreement satisfies the intent of Subsection 366.04(5), Florida Statutes’).

Reynolds’ Response, p. 8. The Reynolds assert that the Third District Court’s decision is also supported by Section 366.05(8), F.S.,[13] because:

As part of the ‘Grid Bill’, the [Commission] was given the authority over electric utilities to require expansion of electric utilities in order to correct inadequacies in the reliability of the energy grid. The logical justification of the [Commission] to require installation of necessary facilities is to ensure service to utility customers that are not served or unreliably served.

Reynolds’ Response, p. 9.

The Reynolds claim that they filed this complaint subject to the Commission’s jurisdiction found in Section 366.04, F.S., and pursuant to Commission Rule 25-22.036, F.A.C., which provides that a person may file a complaint before the Commission complaining of an act or omission by a person subject to Commission jurisdiction which affects the complainant’s substantial interests, and which violates a statute enforced by the Commission, or any Commission rule or order. According to the Reynolds, they did not file the complaint as a party to the Territorial Agreement, but as a person complaining of Keys Energy’s failure to comply with the Commission’s Order approving Keys Energy’s service territory.

Analysis

As discussed above, Rule 25-22.036(2), F.A.C., provides that:

A complaint is appropriate when a person complains of an act or omission by a person subject to Commission jurisdiction which affects the complainant’s substantial interests and which is in violation of a statute enforced by the Commission, or of any Commission rule or order. . . .

Rule 25-22.036(3)(b), F.A.C., provides that each complaint shall contain the rule, order, or statute that has been violated, the actions that constitute the violation, the name and address against whom the complaint is lodged, and the specific relief requested. The complaint filed under this rule complies with its provisions. It alleges failure to comply with a Commission order. It alleges that Keys Energy, named as the respondent in the complaint, has failed to provide customers in its service territory with electric service. It requests that the Commission provide relief by holding that the customers are entitled to electric service and ordering Keys Energy to provide it.

The County seems to argue that because the Reynolds are not a direct party to the territorial agreement between Keys Energy and Florida Keys Electric Cooperative that became an order of the Commission, section 7.1 of the agreement precludes them from invoking the terms of the agreement and the Commission’s jurisdiction over it in any fashion. Staff disagrees with this position for substantive reasons, but would note in passing that the County is not a party to the territorial agreement either, and under the County’s reasoning has no right to defend Keys Energy’s interests under it. Staff would also note that the County’s argument is purely academic at this juncture, since Keys Energy has voluntarily contracted with the No Name Key property owners to provide service, has constructed the necessary electric lines, and holds itself out as ready, willing, and able to serve the territory.

Section 6.1 of the territorial agreement, page 12, states:

It is hereby declared to be the purpose and intent of the Parties that this agreement shall be interpreted and construed, among other things, to further the policy of the State of Florida to: actively regulate and supervise the service territories of electric utilities; supervise the planning, development, and maintenance of a coordinated electric power grid throughout Florida; avoid uneconomic duplication of generation, transmission and distribution facilities; and to encourage the installation and maintenance of facilities necessary to fulfill the Parties’ respective obligations to serve the citizens of the State of Florida within their respective service territories.

Section 4.1 of the Agreement states, at page 11:

The Parties recognize that the Commission has continuing jurisdiction to review this Agreement during the term hereof, and the Parties agree to furnish the Commission with such reports and other information as requested by the Commission from time to time.

These provisions demonstrate, first, that the territorial agreement was developed and executed subject to the Commission’s regulatory jurisdiction granted by Section 366.04, F.S., and it remains subject to that jurisdiction. It is not a private contract. If it were it would be unlawful as a horizontal division of territory, a per se violation of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1. The Commission’s order approving the agreement is an exercise by the state of its police power for the public welfare. Peoples Gas system Inc. v City Gas Co.,167 So.2d 577 (Fla. 3d DCA 1964), aff’d 182 So. 2d 429 (Fla. 1965). Second, the Commission itself may review the territorial agreement as it sees fit on its own motion, or at the behest of an interested member of the public, in this case a customer of Keys Energy seeking service under the agreement. The Supreme Court said in Peoples Gas v. Mason, 187 So. 2d. 187, 189 (Fla. 1966):

Nor can there be any doubt that the commission may withdraw or modify its approval of a service area agreement, or other order, in proper proceedings initiated by it, a party to the agreement, or even an interested member of the public.

Certainly if the Commission may withdraw or modify its approval of a service area agreement, it may also interpret and enforce its terms. See also West Florida Electric Cooperative Association, Inc. v. Jacobs, 887 So. 2d 1200, 1206 (Fla. 2004), a territorial dispute case where the Court said: “A territorial dispute is a disagreement over which utility will serve a geographic area. Service to an area necessarily means service to a customer.” Likewise, a territorial agreement establishing service to a geographic area necessarily means service to customers in that area.

The Reynolds’ complaint shows that they will suffer, and in fact are suffering, an injury of sufficient immediacy to entitle them to a Section 120.57, F.S. proceeding. They have also shown that their injury, Keys Energy’s failure to provide them electric service, is an injury this proceeding, brought pursuant to the Commission’s jurisdiction under Section 366.04, F.S., is designed to protect. The complaint contains sufficient allegations to establish a cause of action before the Commission, which falls under the Commission’s jurisdictional purview. Taking all allegations as true, and interpreting them in the light most favorable to the Reynolds, the complaint states a cause of action upon which the Commission can grant relief. Staff recommends that the County’s Motion to Dismiss should be denied.

Issue 3:

Does the Commission have jurisdiction to resolve the Reynolds’ complaint?

Recommendation:

Yes. The Commission has jurisdiction to resolve the Reynolds’ complaint, and that jurisdiction is exclusive and preemptive. (M. Brown)

Staff Analysis:

Introduction

On April 19, 2013, the Complainants the Reynolds, Monroe County, and Alicia Roemmele-Putney filed briefs in response to the Prehearing Officer’s Order Establishing Schedule for Briefs on Certain Legal Issues, Order No. PSC-13-0141-PCO-EM. The No Name Key Property Owner’s Association filed a Notice of Joinder in the Reynolds’ brief. The individual briefs’ responses to Issues 3 and 4 are summarized below, to avoid repetition.

The Reynolds’ Brief

The Reynolds assert that the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction to resolve their complaint against Keys Energy. Relying upon the Third District Court of Appeal’s decision in Roemmele-Putney, supra, the Reynolds assert that the question of whether the Commission has jurisdiction to resolve their complaint was affirmatively resolved in that case. There the Third District determined that declaratory and injunctive relief was not available to the County and private landowners to establish “that the prospective electrification of No Name Key is regulated – or even precluded – by the Coastal Barrier Resource Act and the County’s policies and procedures adopted pursuant to the Act.” Roemmele-Putney Id., at 79. The Court concluded that the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction to determine whether Keys Energy should provide electric service to the island, and affirmed the Circuit Court’s dismissal of the County’s claim on the same grounds.

The Reynolds also assert that the Roemmele-Putney decision and the Circuit Court’s decision before it limit the forum in which they may raise their complaint for electric service to the Commission:

Reynolds cannot file a complaint in the Sixteenth Judicial Circuit in and for Monroe County because the same subject matter has been dismissed with prejudice. The parties and claims in the above-styled action are the same as those brought by the County in Roemmele-Putney, the Reynolds simply seek a different conclusion. The Reynolds would be barred based on collateral estoppel from bringing these claims before any other Court, having already successfully argued before the Sixteenth Judicial Circuit and the Third District Court of Appeal that the Sixteenth Judicial Circuit does not have jurisdiction over the claim. . . .

Reynolds Brief, pps 9-10.[14]

The Reynolds claim that they and No Name Key property owners are entitled to receive electrical power from Keys Energy under the terms of Order 25127 approving the 1991 Territorial Agreement, and they are currently being denied access to commercial electric power from Keys Energy. They assert that there is no question that Keys Energy’s service area includes No Name Key, and they assert, citing West Florida v. Jacobs, supra, that Keys Energy’s service area is more than simply lines on a map. It is made up of Keys Energy’s current and potential customers.

Referring to Section 6.1 of the Territorial Agreement, the Reynolds state that:

It is the policy of the State of Florida to (1) actively regulate and supervise the service territories of electric utilities; (2) supervise the planning, development, and maintenance of a coordinated electric power grid throughout Florida; (3) avoid uneconomic duplication of generation, transmission and distribution facilities; and (4) to encourage the installation and maintenance of facilities necessary to fulfill electric utilities’ respective obligations to serve the citizens of the State of Florida within their respective service areas.

Reynolds Brief, p. 15. The Reynolds assert that these policies conflict with Monroe County’s ordinance purporting to prohibit the extension of electric lines to No Name Key. They believe that if the Ordinance prevails, and county and municipal governments can prohibit extension of electric facilities to certain locales, the Commission would be unable to actively supervise a coordinated power grid and the service territories of utilities. They refer to Florida Power Corporation v. Seminole County and City of Lake Mary, 579 So. 2d 105, 107 (Fla. 1991), where the Supreme Court reasoned that if each local government had authority to dictate the location of electric lines then the Commission’s statewide supervision and control would be nullified:

In the State of Florida there are approximately 100 CBRS [Coastal Barrier Resource System] areas, many of which power lines already travel through or connect to homes in a CBRS unit. By way of example, Saint Joseph Bay, near Tallahassee, is located entirely within a CBRS unit. A determination that Monroe County can prohibit a customer’s connection on No Name Key would set a precedent allowing Gulf County to prohibit extension of utilities to homeowners in Saint Joseph Bay without the oversight of the Commission.

Reynolds Brief, p. 17. The Reynolds also contend that if the Commission does not police the Territorial Agreement it approved in Order No. 25127 and enforce its terms, and instead allows Keys Energy to deny service due to the County’s ordinance, then it would not be actively supervising territorial agreements as antitrust law requires. According to the Reynolds, the County’s argument that the Commission can only settle a territorial boundary dispute between the utility parties to the agreement is contrary to the intent of the antitrust laws, which is to protect the consumer. If the Commission can only police boundaries, then consumers within those boundaries are not protected.

Next the Reynolds argue that the installation of power lines and connection to the lines by customers on No Name Key does not constitute “development” as the County asserts. According to the Reynolds, Section 380.04, F.S., delineates operations or uses of land that are not considered development under that statute. Specifically, they say, “work by any utility and other persons engaged in the transmission of gas, electricity, or water, for the purpose of inspecting, repairing, renewing, or constructing on established rights-or-way any sewers, mains, pipes, cables, utility tunnels, power lines, towers, poles, tracks, or the like” is not development. Section 380.04(3)(b), F.S. The Reynolds also cite the County’s Local Development Regulations (LDRs) governing permits for construction, installation or maintenance of any public or private utility. According to County Ordinance §19-36(6) “It is not the intent of this section to restrict a public or private utility in any way from performing its service to the public as required and regulated by the public service commission or the applicable state statutes.”

The Reynolds conclude with the argument that notwithstanding the Territorial Agreement, they and the property owners on No Name Key are entitled to electric power under the Grid Bill pursuant to Section 366.05(8), F.S. They argue that Section 366.05(8), F.S., which provides that the Commission can require installation or repair of necessary facilities where it believes inadequacies exist in the energy grids developed by the electric industry, includes distribution facilities:

When, as here, the residents of an entire geographic area are being denied access to the electric grid, the PSC has the authority, under the Grid Bill, to require that the necessary facilities be constructed in order to tie that area into the State’s power grid.

Reynolds brief, p. 23. The Reynolds conclude their brief with the assertion that the Commission has jurisdiction over their complaint, and they and No Name Key property owners are entitled to receive electric power from Keys Energy under the provisions of Order No. 25127.

The County’s Brief

In the introduction to its brief, the County states that No Name Key is an Area of Critical State Concern within the meaning of Section 380.05, F.S. Parts of No Name Key are within the Key Deer Refuge managed by the United States Fish & Wildlife Service, which regulates development on the island pursuant to the Endangered Species Act. According to the County, its 2010 Comprehensive Plan (Comp. Plan), adopted in 1996 and approved by the Department of Community Affairs (DCA) in 1997, includes specific provisions to protect the Keys, including No Name Key. The County has adopted ordinances and regulations implementing the Comp. Plan that prohibit the extension of electric lines and other public utilities to or through any lands designated as a unit of the Federal CBRS and the County’s CBRS Overlay District where No Name Key is located. Monroe County Code § 130-122 (b) provides: “Within the overlay district, the transmission and/or collection lines of the following types of public utilities shall be prohibited from extension or expansion: central wastewater treatment collection systems; potable water; electricity, and telephone and cable.” The County explains that it filed its complaint for declaratory relief in the Sixteenth Judicial Circuit regarding its ability to enforce its ordinances, including this one, against Keys Energy and all the property owners on No Name Key with existing residences. As described in the case background above, the Circuit Court dismissed that action with prejudice, holding that the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction to resolve the issues raised in that case. The Circuit Court’s opinion was upheld by the appellate court in Roemmele-Putney.

The County states that it is responsible for the enforcement of state and local laws and its own ordinances. It argues that the Commission has no statutory authority under Chapter 366 to impose an obligation to serve on an “electric utility” like Keys Energy as it does have over privately owned “public utilities.” The County refers to the Complaint of Lee County Electric Cooperative v. Seminole Electric Cooperative, Inc.,[15] where the Commission stated that:

This Commission’s powers and duties are only those conferred expressly or impliedly by statute, and any reasonable doubt as to the existence of a particular power compels us to resolve that doubt against the exercise of such jurisdiction.

County Brief, p. 9.

As it argued in its Motion to Dismiss the Reynolds complaint, the County claims that the Territorial Agreement is a contract exclusively between Keys Energy and the Florida Keys Electric Cooperative and excludes any other party from asserting any rights under it. The County asserts that there is no justiciable issue between the two utilities, and there is no territorial dispute to resolve, and therefore the Commission does not have jurisdiction to resolve the complaint.

In this instance Monroe County is not, in any way, seeking to usurp the PSC’s jurisdiction: the County is not attempting to regulate the service territories of KES or FKEC, or any other matter within the PSC’s jurisdiction. Rather, the County is attempting to protect the Florida Keys, an Area of Critical State Concern, from the adverse impacts of development and to protect ’the public health, safety, and welfare of the citizens of the Florida Keys and maintaining the Florida Keys as a unique Florida resource,’ Section 380.552(7)(n), F.S.

County Brief, p. 6.

The County argues that no provision of the Commission’s enabling statutes, Chapter 366, F.S., preempts the County Comprehensive Plan and its ordinances implementing it. According to the County, Sections 366.01 and 366.04(1), F.S., only apply to public utilities, not electric utilities and thus provide no statutory basis for preempting the County’s ordinances. The County also argues that preemption is not applicable in this case because:

The PSC’s authority under the Grid Bill is limited to the ‘planning, development and maintenance of a coordinated electric grid’ and the prevention of ‘uneconomic duplication of generation, transmission and distribution facilities’ neither of which are at issue in this case and because there is no territorial dispute at issue in this case.

County Brief, p. 15.

The County asserts that its enforcement of its ordinances will not impair the Commission’s ability to actively supervise utilities subject to its regulatory jurisdiction for the purpose of preventing anti-competitive behavior and preserving state action immunity. According to the County, the ordinances do not prohibit the Commission from enforcing territorial agreements between the parties or inhibit the Commission from resolving any real territorial dispute. The County also argues that Commission Rule 25-6.105, F.A.C., contemplates that a utility may refuse to provide service where doing so would involve “violation of any state or municipal law or regulation governing electric service.” According to the County:

It is obvious on its face that the Commission would not have adopted a rule that would have vitiated its ability to supervise utilities for antitrust purposes, and the cited PSC rule thus demonstrates that compliance with a valid state or local government law governing electric service cannot impair the PSC’s ability to fulfill its antitrust law obligation.

The County concludes by stating that the Commission should respect its Comprehensive Plan and LDRs and dismiss the Reynolds’ complaint with prejudice.

Ms. Roemmele-Putney’s Brief

Ms. Roemmele-Putney’s positions in her brief are consistent with the County’s positions. She contends that the Commission does not have jurisdiction to resolve the Reynolds’ complaint because the relief requested, that it order Keys Energy to provide service is not within the Commission’s statutory authority. According to Ms. Roemmele-Putney, the Commission’s jurisdiction is not a basis for exercising jurisdiction over the complaint, because there is no dispute regarding the area the parties to the agreement are to serve, and the Commission has no statutory authority to require a municipal utility such as Keys Energy to provide service to customers. According to Ms. Roemmele-Putney the utility parties to the agreement cannot confer authority on the Commission by contract. United Telephone Co. of Florida v. Public Service Comm’n, 496 So. 2d 116 (Fla. 1986).

Ms. Roemmele-Putney also argues, as the County does, that no customer has standing under the Territorial Agreement to demand electric service. Ms. Roemmele-Putney cites an earlier case involving the proposed electrification of No Name Key, Taxpayers for the Electrification of No Name Key, Inc. v. Monroe County and City Electric Service, Case No. 99-819-CA-18, Amended Order Granting Summary Judgment (Fla. 16th Cir. June 11, 2003), which held that the plaintiffs had no statutory or property rights to have electric power extended to their homes.[16]

Like the County, Ms. Roemmele-Putney argues that a finding by the Commission that it does not have jurisdiction to resolve the Reynolds’ complaint does not place Keys Energy or the Florida Keys Electric Cooperative in jeopardy of antitrust liability, because:

Just as there is no territorial dispute here, there is no potential antitrust claim here either, because no entity is attempting to restrain competition. The only ‘restraint’ in this case results from the application of the County’s lawful ordinances that were enacted to protect a designated environmentally sensitive area from the adverse consequences of additional development. Thus the denial of jurisdiction in this case would not jeopardize the Commission’s authority to approve, supervise, and enforce territorial agreements because there is no issue relating to the approval, supervision, or enforcement of the Territorial agreement between [Keys Energy] and [Florida Keys Electric Cooperative] present in the instant complaint.

Roemmele-Putney Brief, p. 14. Ms. Roemmele-Putney concludes that the Commission should deny the Reynolds’ complaint with prejudice.

Analysis

The Reynolds, property owners on No Name Key, have filed this complaint asking the Commission to find that they are entitled to receive electric service from Keys Energy under the terms of the territorial agreement approved by Order No. 25127. Clearly No Name Key lies in Keys Energy’s service area under the agreement. As the case has progressed, Keys Energy, with assurances from the United States Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service (Attachment B), has constructed facilities to No Name Key to fulfill its obligation to serve, but has been unable to connect because the County has resisted. The County asserts that its ordinances prohibit electric lines on the island and it has refused to issue building permits to No Name Key customers to hook up to Keys Energy’s facilities. The question becomes who has jurisdiction to decide whether the current residents of No Name Key can receive electric service from Keys Energy: the Commission, or the County? Staff recommends that the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction to make this determination, and that jurisdiction is preemptive.

The Commission is the administrative agency authorized by the Florida Legislature, through Chapter 366, F.S., to oversee the provision of electric service throughout the state of Florida. The Legislature has stated that the regulatory authority granted to the Commission in Chapter 366 is:

. . . in the public interest and this chapter shall be deemed to be an exercise of the police power of the state for the protection of the public welfare and all the provisions hereof shall be liberally construed for the accomplishment of that purpose.

Section 366.01, F.S. The powers of the Commission include the jurisdiction “[t]o require electric power conservation and reliability within a coordinated grid throughout Florida for operational and emergency purposes,” and “[t]o approve territorial agreements between and among rural electric cooperatives, municipal electric utilities, and other electric utilities under its jurisdiction.” Section 366.04(2)(c) and (d), F.S. The statute provides that:

[t]he jurisdiction conferred upon the commission shall be exclusive and superior to that of all boards, agencies, political subdivisions, municipalities, towns, villages, or counties, and, in each case of conflict therewith, all lawful acts, orders, rules and regulations of the commission shall in each instance prevail.

Section 366.04(1), F.S.

Both the Sixteenth Judicial Circuit (twice) and the Third District Court of Appeal have ruled that the Commission has jurisdiction to decide this question. In Roemmele v. Putney, supra at 83, the Third District stated:

The appellees and the PSC also have argued, and we agree, that KES’s existing service and territorial agreement (approved by the PSC in 1991) relating to new customers and ‘end use facilities’ is subject to the PSC’s statutory power over all ‘electric utilities’ and any territorial disputes over service areas, pursuant to section 366.04(2)(e), Florida Statutes (2011). The PSC’s jurisdiction, when properly invoked (as here), is ‘exclusive and superior to that of all other boards, agencies, political subdivisions, municipalities, towns, villages, or counties.’ §366.04 (1). Section 4.1 of the 1991 KES territorial agreement approved by the PSC expressly acknowledges the PSC’s continuing jurisdiction to review in advance for approval or disapproval any proposed modification to the agreement.

The Third District concluded:

The Florida Legislature has recognized the need for central supervision and coordination of electrical utility transmission and distribution systems. The statutory authority granted to the PSC would be eviscerated if initially subject to local governmental regulation and circuit court injunctions sought by Monroe County.

The Third District’s decision is supported by a long line of Florida Supreme Court cases holding that the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction over electric service territorial agreements between all utilities, which become part of the Commission’s orders approving them. See, e.g. Storey v. Mayo, 217 So. 2d 304 (Fla. 1968); City Gas Company v. Peoples Gas System, Inc., 182 So. 2d 429 (Fla. 1965) (“In short, we are of the opinion that the commission’s existing statutory powers over areas of service, both expressed and implied, are sufficiently broad to constitute an insurmountable obstacle to the validity of a service area agreement between regulated utilities, which has not been approved by the commission.”); City of Homestead v. Beard, 600 So. 2d 450 (Fla. 1992). As the Supreme Court held in Public Service Commission v. Fuller, 551 So. 2d 1210, 1212 (Fla. 1989) any interpretation, modification or termination of an order approving a territorial agreement:

. . . must first be made by the [Commission]. The subject matter of the order is within the particular expertise of the [Commission], which has the responsibility of avoiding uneconomic duplication of facilities and the duty to consider such decisions on the planning, development, and maintenance of a coordinated electric power grid throughout the State of Florida. The [Commission] must have the authority to modify or terminate this type of order so that it may carry out its express statutory purpose.

The Commission’s order approving the agreement is an exercise by the state of its police power for the public welfare. Peoples Gas system Inc. v City Gas Co., 167 So.2d 577 (Fla. 3d DCA 1964), aff’d 182 So. 2d 429 (Fla. 1965). The Commission itself may review the territorial agreement as it sees fit on its own motion, or at the behest of an interested member of the public, in this case a customer of Keys Energy seeking service under the agreement. The Supreme Court said in Peoples Gas v. Mason, 187 So. 2d. 187, 189 (Fla. 1966):

Nor can there be any doubt that the commission may withdraw or modify its approval of a service area agreement, or other order, in proper proceedings initiated by it, a party to the agreement, or even an interested member of the public.

Certainly if the Commission may withdraw or modify its approval of a service area agreement, it may also interpret and enforce its terms.

It is important that the Commission have, and fully exercise, its jurisdiction over electric service territorial agreements, not just to approve them in the first instance as a simple geographical boundary, but to actively supervise their implementation and enforce their terms. Territorial agreements are horizontal divisions of territory, considered to be per se Federal antitrust violations under the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1. Parker v. Brown, 317 U.S. 341, 350 (1942) (a territorial agreement effective “solely by virtue of a contract, combination or conspiracy of private persons, individual or corporate, would violate the Sherman Act.”) When territorial agreements are sanctioned by the State, however, they are entitled to state action immunity from liability under the Sherman Act. 317 U.S. at 350; Municipal Utilities Board of Albertville v. Alabama Power Co., 934 F. 2d 1493 (11th Cir. 1991). Entitlement to state action immunity is demonstrated by a “clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed state policy” encouraging the activity in question, and “the policy must be actively supervised by the State itself.” California Retail Liquor Dealers Ass’n v. Midcal Aluminum, 445 U.S. 97, 105 (1980). See also Praxair, Inc. v. Florida Power & Light Co., 64 F. 3d 609 (11th Cir. 1995), where the Court held that two Florida electric utilities were entitled to state action immunity from antitrust liability for their territorial agreement because Chapter 366, F.S., demonstrated a clearly articulated and affirmatively expressed state policy to regulate retail electric service areas, and the Commission’s extensive control over the validity and effect of territorial agreements indicated active state supervision of the agreements. If the Commission cannot decide who can receive electric service in territory covered by a territorial agreement, and in contravention of its terms, it could be argued that the Commission is without power to enforce its own orders and actively supervise the agreements it has approved. This result could place electric utilities who are parties to territorial agreements throughout the state in jeopardy of antitrust liability.

The County and Ms. Roemmele-Putney dismiss this concern with the argument that there is no anticompetitive behavior demonstrated by Keys Energy and Florida Keys Electric Cooperative in this case, but the Commission’s charge under antitrust law extends beyond the policing of any particular anticompetitive behavior. The Commission must demonstrate continued, meaningful, active supervision of the State’s policy to displace competition between electric utilities throughout the state by approving – and enforcing – territorial agreements and resolving disputes. An agreement and Order that the Commission cannot enforce in any substantive way will not satisfy the state action immunity doctrine under Parker v. Brown and Midcal.[17]

For the reasons explained above, staff recommends that the Territorial Agreement the Commission approved in Order No. 25127 was developed and executed subject to the Commission’s regulatory jurisdiction granted by Section 366.04, F.S., and it remains subject to that jurisdiction. It, and the Commission order approving it, govern the issue of whether the Reynolds and No Name Key Property Owners are entitled to receive electric power from Keys Energy, and the Commission has exclusive jurisdiction to make that determination.

Issue 4:

Are the Reynolds and No Name Key property owners entitled to receive electric power from Keys Energy under the terms of the Commission’s Order No. 25127 approving the 1991 territorial agreement between Keys Energy and the Florida Keys Electric Cooperative?

Recommendation:

Yes. The Reynolds and No Name Key Property Owners are entitled to receive electric power from Keys Energy under the terms of the Commission’s Order No. 25127. (M. Brown, Rieger)

Staff Analysis:

As mentioned above, under established law, a territorial agreement between two electric service providers becomes part and parcel of the Commission’s order approving it, because otherwise it would be a purely private contract, a horizontal division of territory violative of the Sherman Antitrust Act. As discussed in the staff analysis of the County’s Motion to Dismiss, staff does not believe Section 7.1 of the territorial agreement precludes the Reynolds and the No Name Key Property Owners from invoking its terms in their complaint for electric service from Keys Energy. The Territorial Agreement is not, and cannot be a purely private contract between the utilities. The Commission itself may review the territorial agreement as it sees fit on its own motion, or at the behest of an interested member of the public, in this case a customer of Keys Energy seeking service under the agreement. While case law holds that an electric utility customer does not have a right to receive electric service from the service provider of his or her choosing,[18] it says nothing about a customer seeking the initiation of service under a territorial agreement in the first place. As Peoples Gas v. Mason, supra indicates, the Commission may withdraw or modify its approval of a service area agreement where the public interest requires, and similarly, it may also interpret and enforce its terms. Section 4.1 of the Territorial Agreement specifically contemplates a continuing Commission review of its implementation.

While the County and Ms. Roemmele-Putney dismiss the language of Section 6.1 of the Territorial Agreement as “surplussage,” in that section the parties clearly acknowledge an obligation to provide service in their respective territories. Section 6.1 states:

It is hereby declared to be the purpose and intent of the Parties that this agreement shall be interpreted and construed, among other things, to further the policy of the State of Florida to: actively regulate and supervise the service territories of electric utilities; supervise the planning, development, and maintenance of a coordinated electric power grid throughout Florida; avoid uneconomic duplication of generation, transmission and distribution facilities; and to encourage the installation and maintenance of facilities necessary to fulfill the Parties’ respective obligations to serve the citizens of the State of Florida within their respective service territories.

As the Third Circuit Court of Appeal held in Roemmele-Putney, the Territorial Agreement is subject to the Commission’s regulatory authority under Section 366.04, F.S. The plain language of Section 6.1, which the Commission incorporated in its Order No. 21257 indicates that Keys Energy will provide service to the citizens of the State of Florida within its service territory. Staff recommends that a plain reading of that section demonstrates that the Reynolds and No Name Key property owners are entitled to receive electric power from Keys Energy by the terms of the Commission’s Order No. 25127.

Issue 5:

How should the Commission dispose of the Reynolds’ complaint?

Recommendation:

The Commission should grant the ultimate relief the Reynolds have requested and order that the customers located on No Name Key in Keys Energy’s service territory are entitled to receive electric service from Keys Energy. The Commission should find that its determination of the issues in the Reynolds complaint is exclusive and preemptive. (M. Brown, Rieger)

Staff Analysis:

As stated above, staff recommends that the Territorial Agreement the Commission approved in Order No. 25127 controls the disposition of the Reynolds complaint for electric service from Keys Energy. It provides in clear and direct terms that Keys Energy will provide service to customers within the territory approved in the Order. Keys Energy has complied with the terms of Order No. 25127. It has constructed the facilities needed to provide electric service to No Name Key, in accordance with its contract for service with the No Name Key property owners, and in accordance with the direction of the United States Fish and Wildlife Commission. It holds itself out as ready, willing and able to serve, and it should be permitted to do so, as the Commission has authorized.

Order No. 25127 is an exercise of the Commission’s jurisdiction under its enabling statutes in Chapter 366, F.S. The Legislature has declared that jurisdiction to be “exclusive and superior to that of all other boards, agencies political subdivisions, municipalities, towns, villages, or counties, and, in case of conflict therewith, all lawful acts, orders, rules, and regulations of the commission shall in each instance prevail.”[19] Section 364.01, F.S. This would include the County’s Comprehensive Plan and any local ordinances implementing it.

While it is not the Commission’s place to direct the County to act in any way with respect to its ordinances in this case, staff would point out that the United States Fish and Wildlife Service has indicated that the Key Deer and other endangered species will not be harmed by the installation of power lines, if constructed properly. Staff would also emphasize that this recommendation does not suggest authorization of further development on the island, which is within the County’s purview.

For the reasons explained above, staff recommends that the Commission should grant the Reynolds complaint and find that they and the No Name Key property owners are entitled to receive electric service from Keys Energy.

Issue 6:

Should this docket be closed?

Recommendation:

If the Commission denies staff’s recommendation in Issue 2, this docket should be closed. If the Commission grants staff’s recommendation in Issue 2, and if no person whose substantial interests are affected by the proposed agency action files a protest of Issues 3-5 within 21 days of the issuance of the Order, this docket should be closed. (M. Brown)

Staff Analysis:

If the Commission denies staff’s recommendation in Issue 2, this docket should be closed. If the Commission grants staff’s recommendation in Issue 2, and if no person whose substantial interests are affected by the proposed agency action files a protest of Issues 3-5 within 21 days of the issuance of the Order, this docket should be closed. (M. Brown)

[1] The Reynolds filed a second amended complaint to correct a scrivener’s error on March 20, 2013.

[2] Monroe County was granted intervention in the docket on May 22, 2012, by Order No. PSC-12-0247-PCO-EM. The No Name Key Property Owners Association was granted intervention on September 11, 2012, by Order No. PSC-12-0472-PCO-EM, and its renewed petition to intervene was granted on April 19, 2013, by Order No. PSC-13-0159-PCO-EM. Ms. Alicia Roemmele-Putney’s amended petition to intervene was denied on April 19, 2013, by Order No. PSC-13-0161-PCO-EM.

[3] The Association filed a Notice of Joinder in the Reynolds’ opposition on April 10, 2013.

[4] Monroe County v. Utility Board of the City of Key West d/b/a Keys Energy Services, Case No. 2011-CA-342-K

[5] Order No. PSC-13-0141-PCO-EM, issued March 25, 2013.

[6] In his order denying Ms. Roemmele- Putney intervention as a full party to the proceeding, the Prehearing Officer ruled that she could file a brief on the legal issues if she chose to do so.

[7] See Order No. 25127, attached to the Complaint as Exhibit A, which attaches the Territorial Agreement and incorporates it by reference.

[8] See Monroe County Ordinance 043-2001, adopted December 19, 2001, attached to the Complaint as Exhibit B, and the Monroe County Planning Commission Resolution No. P 61-01, adopted September 26, 2001, attached to the Complaint as Exhibit C.

[9] The County made this same argument in its Opposition to the Association’s Renewed Petition to Intervene. The Prehearing Officer granted intervention to the Association subject to the Commission’s decision on the County’s Motion to dismiss the Complaint.

[10] Agrico Chemical Co. v. Dept. of Environmental Regulation, 406 So. 2d 478. Under that standard, a party must show that they will suffer an injury in fact to a substantial interest the proceeding is designed to protect.

[11] Supra. At p. 2

[12] Section 366.04(5), F.S. provides:

The commission shall further have exclusive jurisdiction over the planning, development, and maintenance of a coordinated electric power grid throughout Florida to assure an adequate and reliable source of energy for operational and emergency purposes in Florida and the avoidance of further uneconomic duplication of generation, transmission, and distribution facilities.

[13] Section 366.04(8), F.S. provides:

If the commission determines that there is probable cause to believe that inadequacies exist with respect to the energy grids developed by the electric utility industry, including inadequacies in fuel diversity or fuel supply reliability, it shall have the power, after proceedings as provided by law, and after a finding that mutual benefits will accrue to the electric utilities involved, to require installation or repair of necessary facilities, including generating plants and transmission facilities, with the costs to be distributed in proportion to the benefits received, and to take all necessary steps to ensure compliance.

[14] The Reynolds also claim that the Commission is estopped from determining that it does not have jurisdiction over this subject matter, because it argued in favor of its exclusive jurisdiction as Amicus Curiae before the Sixteenth Judicial Circuit and the Third District Court of Appeal in Roemmele-Putney. This claim has no merit. The Commission was not a party litigant in those proceedings. The Commission, as it argued before those Courts, and as the Third District found, has jurisdiction to determine its jurisdiction in the first instance. It is the court (tribunal) of competent jurisdiction to decide this case, and it cannot be precluded from a full review of all the issues before it. Florida Public Service Commission v. Bryson, 569 So. 2d 1253. (Fla. 1990).

[15] Order No. PSC-01-0217-FOF-EI, issued January 23, 2001, affirmed in Lee County Elec. Coop., Inc. v. Jacobs, 820 So. 2d 297, 300 (Fla. 2001).

[16] Staff would note that Ms. Roemmele-Putney indicates in her citation to Taxpayers for Electrification that the Court’s decision was subsequently vacated on agreed motion of the parties.

[17] Staff also disagrees with the argument that Rule 25-6.105(5), F.A.C., somehow protects utilities from antitrust liability. The rule states, in pertinent part;

As applicable each utility may refuse or discontinue service under the following conditions;

(a) For non-compliance with or violation of any state or municipal law or regulation governing electric service.

The rule does not include county ordinances. If it did, it would say so.

[18] See, Storey v, Mayo, supra.; Lee County Electric Co. v. Marks, 501 So. 2d 1159 (Fla. 1976).

[19] The County and Ms. Roemmele-Putney imply that the express preemption language in Section 366.04(1), F.S., applies only to the Commission’s jurisdiction over investor-owned public utilities. The language applies to all jurisdiction granted to the Commission in Section 366.04, F.S., and Chapter 366, F.S., generally.